George Caley was born on the 10 June 1770 at Craven, Yorkshire, England. He was taken out of school at the age of fourteen to work as a stable boy in his father’s stables as his father was a horse dealer. Working with horses included learning how to prepare certain herbs to prepare horse medicines, and this included a small amount of botany. This introduction to botany led to a further interest in botany, which resulted in Caley applying to one of England’s most prominent botanists, Sir Joseph Banks, for a position. Sir Joseph Banks was not only a botanist but also a natural historian who took part in Captain James Cook's voyage from 1768 to 1771. He was also the president of the Royal Society for over 40 years.

After working at one of the most significant gardens in the world, the Kew Gardens in London England, Sir Joseph Banks appointed Caley in 1798 as a botanical collector in the new Colony of New South Wales.

Caley arrived in New South Wales in April 1800 on the Speedy. Until his return to England in 1810 he spent the next ten years extensively exploring which included Jervis Bay, the Hunter River, Norfolk Island, Van Diemen's Land, and in Sydney in 1804 the Vaccary Forest (Cowpastures), the Nepean and Camden, and an attempted crossing of the Blue Mountains. He also contributed to scientific work and collections and wrote extensive accounts of all the proceedings that he witnessed and wrote a substantial amount of letters. He also formed lasting friendships which included the famous Parramatta scientist George Suttor, but he also formed some fractious relationships which included Samuel Marsden the Minister of Parramatta’s St. Johns Cathedral. One of the most important relationships and enduring friendships of his life and career was formed whilst in Parramatta with the Darug boy Daniel Moowattin.

In May 1800 Governor Philip Gidley King advised Sir Joseph Banks that he had fixed George Caley in Parramatta. For the first few months after arriving in Parramatta Caley lived in a cottage close to Government House in what had been according to George Suttor’s diary: “Governor Phillip’s cottage, a little above the dam”. He was also allowed the use of a room in Government House to dry out and preserve his collections. Governor King planned a botanic garden at Old Government House under Colonel William Paterson’s direction, and it is assumed that Caley would have largely managed this garden, but there is no official correspondence confirming this.

By September 1800 a hut had been specifically built for him to the north-east of Government House, bordered by O’Connell and Marsden Streets. The land was leased to Caley on the 1 January 1806. It was: “1 acre, 2 roods and 18 rods on the north side of the Parramatta River. Rent; 10 shillings per year for 7 years commencing from date”.

A description of his cottage at the point of sale in 1810 read:

“TO be Sold by Private Contract, a Weather-boarded and Shingled Dwelling House, having an extensive garden under cultivation, and other conveniences, most eligibly situate at the upper end of Parramatta, contiguous to a stream of fresh water, and in the present occupation of George Caley. The whole held under Lease of which 3 years are unexpired. Also to be Sold, a few useful articles, comprising a feather bed, steel mill, kitchen requisites, some iron, &c. &c.— For further particulars apply on the Premises”.

Caley maintained a botanical garden and nursery on this site and he started a garden to grow vegetables as there were very few vegetables to eat. Upon arriving in Parramatta Caley noted:

“The general mode of living is very mean and wretched, many having nothing but the store allowance…vegetables, upon an average, are very scarce. Tea seems to be the greatest indulgence”.

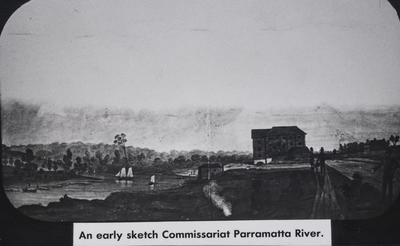

One of the major reasons for the poor supply of food was that supplies were controlled through the Government Store, also called the Commissariat. It supplied not only food, but also clothing and tools. Caley consistently criticized the impact its role was having on the colony: “Many that are sick are hastened to the grave for want of proper nourishment, for as the constitution is debilitated by bad food, it must not be expected to be restored again by medicine alone, or without the other”.

An early sketch Commissariat Parramatta River. Source: Parramatta Heritage Centre Research Library photographic collection, LSP00748

After the sale of Caley’s cottage in 1810 Governor Sir Thomas Brisbane granted part of this lease to the Agricultural Society as a place where experimental gardening could take place. The Old King’s School was later built on this site and students started attending the school in 1836.

George Caley had a reputation for being independent minded and defiant. Sir Joseph banks once said of him in a letter to Governor King: “Had he been born a Gentleman he would have been shot long ago in a Duel”. Once on the road between Parramatta and Sydney George Caley did not remove his hat when the prominent Captain Anthony Fenn passed him in his carriage. This incident highlights his determination not to acknowledge hierarchy when it did not suit him. There was said to be a proverb in New South Wales at the time that Joseph banks reported to Governor Lachlan Macquarie that: “Caley and the common hangman are the only two people who do as the please”. This independent perspective also allowed him to acknowledge the strengths and particular superiority of the Aboriginal people. In 1803 referring to recent incidents of civil strife Caley commented:

“In some attempts that we made to take them by surprise, they completely duped us. I shall not hesitate to say that had they been bent for to do us as much injury as we would have done to them, the matter would not have ended so well; for it was in their power to have done us almost an irreparable injury by fire, as the colony was so badly off for the want of provisions. Whether the natives were guilty of what was laid to their charge I shall not say; but there has been proof of the stockkeepers losing a part of their flock and laying the charge to the natives, when at the same time they were innocent”.

Caley also maintained a longstanding friendship with the Darug boy Daniel Moowattin who acted as his guide and translator.

Not long after his arrival in New South Wales Caley noted that: “The best public building in the colony is a new church at Parramatta, which is not yet finished”. Samuel Marsden, who was the Minister of St. John’s Cathedral for nearly fifty years, had many interactions with Caley, often difficult. In November 1801 Marsden requested that the convict Joseph Charrington - who was assigned to Caley - apprehend some Aboriginal people against their will. Charrington complained to Caley who then confronted Marsden. Marsden responded with: “what was Sir Joseph Banks’ plants and bother to the welfare of the colony?” Caley withdrew in response to that statement but discovered the next day that his convict was in prison. Caley angrily confronted Marsden and that evening Charrington was released, but the relationship between Marsden and Caley was forever strained.

As the population grew so did the need for more wind and water powered mills to grind cereal crops. In Parramatta a government watermill was constructed using the Parramatta River as its source of energy. George Caley’s and Samuel Marsden’s homes adjoined this site and both men were deeply involved in the progress of this watermill with Marsden having been appointed Superintendent of Works by the government. The mill brought the two men into further conflict with each other, and Caley in 1806 wrote ‘An account of a water-mill erected at Parramatta in New South Wales’ which was very critical of Marsden’s involvement. The arguments extended to Marsden accusing Caley of allowing his dogs to come into his garden and disturb his pet rabbits – an accusation denied by Caley.

During his time in Parramatta Caley experienced an earthquake. He later reported to Sir Joseph Banks that: “About 11 o’clock at night on 12th February, 1801, I was awoke by an earthquake, which gave repeated shocks for about three minutes, though in other places not far from me it was said not to last above a few seconds. At Sydney I believe it was but little felt…It came from the east and proceeded to the west – that is, it began at the eastern end of the house and went off at the western. It first began like thunder at a distance, and shortly after the floor began to move under me with such violence as I think would have thrown me down had I been standing up or walking. Fortunately, no farther damage was done than a few brick houses a little shattered”.

In 1810 George Caley returned to England with his friends Daniel Moowattin and George Suttor on the Hindostan . Also on the trip was Caley’s pet cockatoo named Jack. For six years Caley he was the Curator of the Botanic Gardens in St. Vincent in the West Indies.

Having spent ten years in Parramatta he accomplished a great deal. He sent many specimens to Sir Joseph Banks in England, widely expanding the world’s awareness of Australia’s unique flora and fauna, and through his explorations, scientific curiosity and commentary on the new colony, he left a significant legacy. The famous Parramatta clergyman and botanist William Woolls wrote on Caley in 1886: “His collection of Australian birds gave Caley a European reputation. They were admired by all lovers of natural history, and though the King of Prussia offered him 350 pounds for them, he refused the money…He married a widow Mrs. Wise, and in the course of events, his step-daughter became the wife of the Rev. John McKenny, formerly superintendent of the Wesleyan missions, and for a time also a resident of Parramatta.”

George Caley died in Bayswater, England, on the 23 May 1829.

![]()

Caroline Finlay, Regional Studies Facilitator, Parramatta Heritage Centre, City of Parramatta, 2020

References

Wikipedia. (2020). Joseph Banks. In Wikipedia. Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Banks

Australian Dictionary of Biography. (2020). Caley, George (1770–1829). Retrieved from http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/caley-george-1866

Historical Records of New South Wales Volume 4. (1979). Lieutenant-Governor King to Sir Joseph Banks. Mona Vale: Lansdown Slattery & Company, p. 82.

Pollon, Francis. (1983). Parramatta, The Cradle City of Australia. Parramatta: The Council of the City of Parramatta, p. 31.

Ryan, R.J. (1981). Lands Grants 1788-1806 – Grants by Governor King. Five Dock: Australian Documents Library Pty. Ltd, p. 249.

Classified Advertising. (1810, March 24). The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, p. 2. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article627956

Historical Records of New South Wales Volume 5. (1979). A short account relative to the proceedings in New South Wales, from the year 1800 to 1803, with hints and critical remarks addressed to Sir Joseph Banks. Mona Vale: Lansdown Slattery & Company, p. 295.

Webb, Joan. (1995). George Caley 19th Century Naturalist. Chipping Norton: Surry Beatty & Sons Pty, Ltd, p. 28.

State Library of NSW. (2020). Letter received by Governor King from Joseph Banks, 24 August 1804. Retrieved from https://www.sl.nsw.gov.au/banks/section-07/series-39

Banks to Macquarie. [13 May 1809]. Letters of George Caley, 1795-1825, transcribed by Joan Webb. Mitchell Library MLMMS 6361, Book 4, p. 98.

Historical Records of New South Wales Volume 5. (1979). George Caley to Sir Joseph Banks – Caley’s account of the Colony 1803. Mona Vale: Lansdown Slattery & Company, p. 300.

Webb, Joan. (1995). George Caley 19th Century Naturalist. Chipping Norton: Surry Beatty & Sons Pty, Ltd, p. 33.

Tatrai, Olga. (1994). Wind & watermills in Old Parramatta. Oatlands: Olga Tatrai, pp. 35-81.

Historical Records of New South Wales Volume 4. (1979). George Caley to Sir Joseph Banks – Parramatta 25th August 1801. Mona Vale: Lansdown Slattery & Company, pp. 513-514.

Parramatta and the Early Naturalists of the Colony. (1886, March 20). The Cumberland Mercury, p. 3. Retrieved from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article248793931